Investing in ETFs vs Individual Stocks

By Dale Gillham

Before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) there was a significant surge in managed funds, largely due to the introduction of compulsory superannuation in 1992. However, investors began questioning the value of these investments, given that many funds under-performed the market or, at best, achieved returns of less than 8 per cent per annum over 10 years.

Following the GFC, many investors became even more disillusioned by the institutional funds and since then we have seen a significant surge in exchange-traded funds (ETF) listing on stock exchanges around the world as a way for the financial services industry to continue to attract money into the market.

The rise in ETFs came about because investors were seeking greater transparency and control over their investments following the fallout from the GFC. They also wanted a simpler way to invest that allowed them to diversify their risk at a lower cost.

However, many investors have now started to question the value of investing in ETFs versus individual stocks.

Which should you invest in ETFs versus individual stocks?

An ETF is a listed managed fund that trades on the stock exchange just like individual stocks. ETFs provide investors with access to different asset classes such as stocks, commodities, bonds, debt or currencies. Similar to an unlisted managed fund, an equity ETF, for example, can be exposed to up to 200 shares or more, which endeavours to replicate the performance of a specific index or benchmark, such as the S&P/ASX 200 index. Although, depending on the asset class, ETFs may benchmark a currency such as the US dollar or a commodity such as gold.

A major consideration for most investors when investing in the stock market is the associated costs of the investment. Consequently, one of the so-called benefits of investing in an ETF is that it provides investors with access to the market at a lower cost than many traditional managed funds. ETFs are also priced more efficiently to the value of the assets in the fund, as they typically operate with an arbitrage mechanism that assists in keeping the share price in line with the value of the underlying assets.

While these attributes make ETFs an attractive proposition, investors are still exposed to the same risks that lead them to jump ship from managed funds during and after the GFC. That’s because investors are still subjected to the fluctuations of the market given that ETFs have to remain fully invested regardless of whether the market is rising or falling. While some would argue that an investor can sell out of an ETF at any time, the unfortunate reality is that most don’t sell assets that are falling in value for fear of losing out.

Tracking the performance of an ETF

Remember, the goal of an ETF is to track an index or benchmark, but similar to the issue with unlisted managed funds, many investors are paying for the privilege of achieving average to below-average returns. Let’s look at an example.

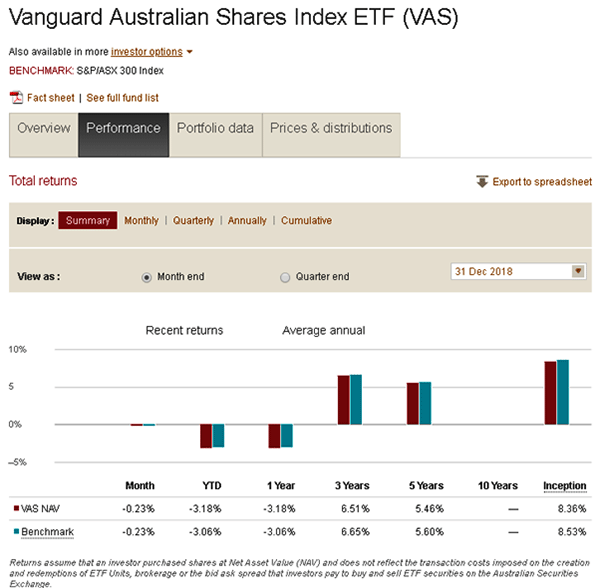

If we review the Vanguard Australian Shares Index ETF (VAS), which is one of the largest ETFs in Australia, you will notice that it has underperformed the S&P/ASX 300 Index, which is the benchmark for this fund, since inception after management fees. If you take a closer look at their disclosure, these returns do not reflect the transaction costs imposed on the creation and redemption of the ETF units, brokerage or the bid-ask spread that investors pay to buy and sell ETF securities on the ASX.

So what does this mean? If these costs were factored in, the returns would be lower than what is presented.

What is even more interesting is that the ETF receives dividends from holding the underlying securities in the fund, which forms part of their total return. Yet the index which they are benchmarking themselves against does not include distributions from dividends. If it did, then the performance of the benchmark would be considerably higher.

The reality is that many investors are happy to turn over their savings to professionals in the hope of achieving better returns than they could on their own. But as this example demonstrates, this is not always the case.

Are you better off investing in individual stocks or ETFs?

For those of you who follow my philosophies, you will know that I favour investing in individual stocks but only if you are prepared to gain, at least, some knowledge to protect your investments. That’s because the number one reason why the majority of traders and investors fail in the stock market is due to a lack of knowledge about how the market works and how to manage investment risk.

According to the financial services industry, one of the major benefits of investing in an ETF is that you can achieve greater diversification than if you invested directly yourself. But as previously demonstrated, this results in a fund holding up to 100 different stocks or more, which not only increases the risk of the portfolio but dilutes investment returns, condemning you to investing mediocrity.

Think about it, you don’t get twice the benefit from holding 20 stocks as you do from holding 10, and you certainly don’t get 10 times the benefit from holding 100 rather than 10. Given this, it seems unrealistic to justify why fund managers would continue holding so many stocks when the diversification benefit is so small.

Unfortunately, the myth surrounding diversification or what I like to call di-worsification is one of the main reasons why investors have to accept lower returns. Because while it is true that diversification reduces risk, a portfolio of shares that is over-diversified is exposed almost exclusively to market risk, which cannot be eliminated by diversification.

Investing in individual stocks

The truth of the matter is that a well-diversified portfolio that allows you to achieve maximum diversification and minimum risk only requires between 5 and 12 stocks in a portfolio, as I outline in my latest book Accelerate Your Wealth – It’s Your Money, Your Choice.

I trade a portfolio of the top 20 stocks on the ASX over 10 years from 2 January 2007, to take into account the effect of the GFC, through to 31 December 2016. And I do this using some very simple trading techniques, such as a trend line and stop loss.

Some of you may be surprised to learn that the gain achieved from capital growth and dividends was 225.82 per cent or an average annual return of 22.58 per cent over the ten years. This equates to an annual compounded rate of return of 12.54 per cent.

So, the view that investing directly in the share market is complex and mysterious, and best left to those profoundly wise and experienced mortals who know what they are doing is a fallacy perpetuated in part by those in the industry who stand to gain from your anxiety and ignorance.

Indeed, many investors have been questioning the conventional wisdom of over-diversification, preferring instead to invest in a concentrated portfolio. The reality is that most investors just want to achieve a good safe return on their investment and a no-holds-barred approach to doing so, which is why many are taking a more active role and investing directly.

Indeed, the choices and benefits of investing directly in individual stocks that are available to the small investor far outweigh the lower returns offered by ETFs and managed funds, which is why I encourage you to read my book, as it will change how you view the market.

Others who read this also enjoyed reading: